When Ashley Merchant was four months pregnant, she and her husband, Mark, put on hold the celebrations they had planned for their baby’s arrival — the baby shower, the hospital visits from family, and the welcome home party. “I wasn’t really sure what the outcome would be, so we kept quiet for a while,” says Ashley. “Things were just not normal or happy for a long time.”

Ashley learned early in her pregnancy that she could face serious challenges. Eight weeks in, an ultrasound test indicated the baby was at risk of a chromosomal, structural or genetic condition. She and Mark were living in Maine at the time and raising their first child, Emmett, but given the complexity of her case, they started searching online for experts in other cities. Many people recommended Dr. Julianne Lauring, an OB-GYN and maternal-fetal medicine specialist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Ashley grew up in the New York area, so when they visited home for Thanksgiving in 2023, she scheduled an appointment.

“Ashley came to my clinic where I have bedside ultrasounds, and as soon as I put the ultrasound on her belly, I knew there were some serious complications that we needed to consider,” says Dr. Lauring. “She told me to do anything we could to give her baby a chance.”

After reviewing the ultrasound and a fetal MRI in November 2023, Dr. Lauring told Ashley and Mark that their baby had a large and complex lymphatic malformation, which is a rare, non-cancerous mass that forms from abnormal lymphatic vessels. The lymphatic system is a vital network of vessels, tissues and organs that transport fluid throughout the body and help protect against infection and disease. The scans showed the lymphatic malformation extending through the back, armpit, neck and throat, and it appeared to be obstructing the airway.

“Dr. Lauring was real with me,” says Ashley. “She promised to try everything to make the best of our situation, even if all she could give us was hope. One of her pieces of advice was to give this fetus a name so we can talk to him. We decided on the name Finnley shortly after that, announcing it on Christmas.”

A Rare and Complex Surgery

Because one of the masses was located in Finnley’s neck, Dr. Lauring contacted Dr. Steven Rosenblatt, a pediatric otolaryngologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital of Children’s Hospital of New York and Weill Cornell Medicine. “It was one of the most complex lymphatic malformations that I’ve seen,” he says. “Many children have lymphatic malformations in the head and neck, but most of these do not cause an airway obstruction. Based on the ultrasounds and fetal MRI scans, there was a real concern that his airway was severely compromised, and we decided we needed to perform an EXIT procedure to keep him safe.”

An EXIT procedure (an acronym for “ex utero intrapartum treatment”) is done in the rare circumstances when a baby is expected to have difficulty breathing after birth. When a baby is in the uterus, it receives oxygen through the placenta. After the delivery, the lungs typically start working to supply oxygen to the body because the placenta is detached — so if an airway obstruction is discovered in utero, the survival of the baby is at risk.

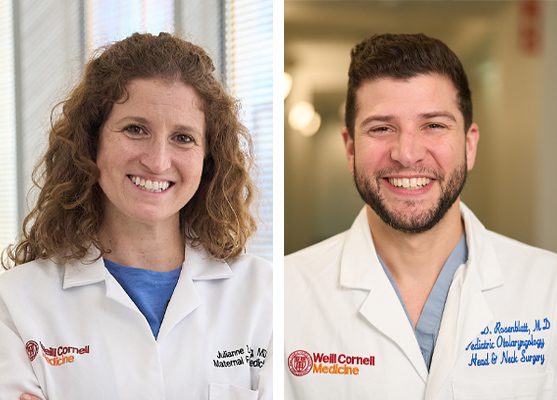

Dr. Julianne Lauring (left) helped plan the complex EXIT (ex utero intrapartum treatment) procedure, in which surgeons would first partially deliver Finnley, giving Dr. Rosenblatt (right) an opportunity to secure Finnley’s airway before he was fully delivered.

Dr. Julianne Lauring (left) helped plan the complex EXIT (ex utero intrapartum treatment) procedure, in which surgeons would first partially deliver Finnley, giving Dr. Rosenblatt (right) an opportunity to secure Finnley’s airway before he was fully delivered.

In an EXIT procedure, surgeons perform a C-section and partially deliver the head, shoulder, neck and part of the chest.

“The remainder of the baby is left inside the uterus,” explains Dr. Rosenblatt. “This is done because we need to trick the body into thinking it is still pregnant while we secure the airway. The connection with the placenta is keeping the baby alive.”

The procedure could pose a risk to both Finnley and Ashley. “Because the uterus is left open while the baby’s airway is secured, our biggest fear for Ashley was excessive bleeding,” says Dr. Lauring. “She might have needed to go to intensive care herself, and there was a small chance she would not survive.”

Finnley’s was the first EXIT procedure at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center in a decade.

Inside the Delivery Room

To prepare for the EXIT procedure, Dr. Lauring started holding monthly planning meetings with a multidisciplinary team that included specialists from obstetric and pediatric anesthesia, neonatology, pediatric otolaryngology, pediatric surgery, hematology, and nursing. “NewYork-Presbyterian is uniquely situated for a case like this,” she says. “We have experts in our fields all working together. We simulated what the process would look like to make sure everyone felt really comfortable if Ashley went into labor.”

Due to the complexity of the case and the number of specialists involved, the team decided it would be safest to perform the EXIT procedure when Ashley was 35 weeks pregnant. This gave the fetus enough time to develop appropriately but minimized the risk of Ashley going into spontaneous labor. As the date grew closer, “it felt really, really scary,” says Ashley. “Mark and I sat my sister down and talked about helping to care for Emmett should I not make it. I wrote him a note about how much I love him.”

The operating room was packed when Ashley was brought in for surgery. “I think we had about 45 people in the OR,” recalls Dr. Lauring. “Right before the case we always do a preoperative huddle, and I’ve never seen a huddle that big. Everyone participated.”

Ashley was put under general anesthesia, and the obstetrics team began the C-section before Dr. Rosenblatt stepped into position. “When you do an EXIT procedure, you have roughly 30 minutes, 45 minutes max, to secure the airway,” he says. “After that, the maternal-fetal circulation will start to fail, and the baby will no longer be able to get oxygen through the umbilical cord and placenta. We knew it was not going to be an easy, straightforward intubation and would require advanced techniques to secure the airway. There was also a chance we would be unable to place a tube through the mouth into the airway, and we might need to access the airway surgically through the neck.”

Scans showed that Finnley’s lymphatic malformation extended through the back, armpit, neck and throat. Doctors knew they would need to work quickly and precisely to secure his airway.

Scans showed that Finnley’s lymphatic malformation extended through the back, armpit, neck and throat. Doctors knew they would need to work quickly and precisely to secure his airway.

Once Finnley was partially out of the uterus, a pediatric anesthesiologist administered medication and a neonatologist applied monitors to track his breathing, heart rate and blood oxygen levels. Dr. Lauring held Finnley around his chest and kept him still. “I remember thinking, ‘Come on, you guys got this. The baby’s got this. You all got this,’” she says.

As soon as Finnley came out, Dr. Rosenblatt used an instrument and a thin, rigid telescope attached to a camera to carefully expose Finnley’s airway and intubate him. “I was able to see his larynx, and that was just a phenomenal moment for me, because I knew I could quickly intubate him,” he says. “I called out, ‘I have the airway’ and I passed a tube into his airway so we could help him breathe. There were some whoops and cheers in the room, and everybody was excited.”

Once the airway was secured, the obstetrics team safely delivered Finnley, cut the umbilical cord and finished the C-section for Ashley. In total, the surgery lasted about two hours. “The opportunity to tell Ashley the baby’s here and alive felt so good,” says Dr. Lauring. “It was really an awesome experience.”

New Treatments, Big Progress

The day after the EXIT procedure, Finnley required a tracheostomy so he could have a safe airway and a feeding tube for nutrition to grow. Over the following four months, he also needed a series of minimally invasive procedures, called sclerotherapy, to shrink the mass because these types of lymphatic malformations usually cannot be removed surgically. Dr. Bradley Pua, a vascular and interventional radiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, is an expert in this technique. He carefully withdraws fluid from the mass using a catheter and injects a medication that causes the tissue to scar, preventing the mass from growing back.

Dr. Bradley Pua performed sclerotherapy to shrink Finnley’s mass after he was born.

Dr. Bradley Pua performed sclerotherapy to shrink Finnley’s mass after he was born.

“Imagine a balloon that’s been filled with water,” explains Dr. Rosenblatt. “If you stick a needle into that balloon, suck all the water out, then squirt in some superglue, the balloon will be stuck shut. That’s essentially what we are doing with sclerotherapy.”

Says Dr. Pua, “Finnley’s case was particularly challenging since his lymphatic malformation wasn’t confined to one spot, but spread across his neck, underarm, and even pressed against his airway, threatening his ability to breathe on his own. Our first priority was giving him back his breath.”

To access the mass in Finnley’s throat, Dr. Pua and Dr. Rosenblatt operated as a team. “The area we needed to access was deep in the neck, so in order to get there from the outside meant we had to traverse through what we describe as ‘tiger country’,” says Dr. Rosenblatt. “You have major arteries, veins, nerves and other anatomic structures that you would not want to pass a needle through. So, the safest way to the back of the throat is through the mouth. Dr. Pua and I used our complementary skills to expose the lesion and perform the sclerotherapy treatment together.”

Ashley and Mark saw dramatic improvement in Finnley after the first two rounds. “He responded very well to sclerotherapy,” says Mark. “I remember the first one that he had, there was a big difference in the size of the mass.”

At five months, Finnley was well enough to meet his big brother Emmett. He was pulling at objects, trying to roll over, and Ashley and Mark heard his first cry.

“Thankfully, the treatment is working incredibly well, but managing this condition will take ongoing care,” says Dr. Pua. “The silver lining: All of these treatments are outpatient, allowing Finnley to heal without being stuck in a hospital.”

A Tiny Hero

When Finnley was six-months old, he finally came home. He still had the tracheostomy tube in place to make sure his airway was clear, but he was making progress, growing and meeting all of his baby milestones.

“Our NewYork-Presbyterian care team keeps growing and they never give up,” says Ashley. “No matter what challenges presented to this team of amazing doctors, they will do whatever it takes to find the exact right care for Finnley every time,” says Ashley.

Finnley, shown here with Ashley, Mark, and big brother Emmett at his first birthday party, is meeting his milestones and thriving at home.

Finnley, shown here with Ashley, Mark, and big brother Emmett at his first birthday party, is meeting his milestones and thriving at home.

“I remember when Finnley was in the NICU and super small, maybe three days old, a nurse told me to write down every win, every little accomplishment,” says Ashley. “I kept this note on my phone, and I would write the date and what Finnley did. Sometimes it was really small like, ‘Could wear a onesie’, and sometimes it was really big like, ‘No more ventilator.’ I’m so grateful for that advice. Now I get to read those notes all the time and see how far he’s come.”

Caring for Ashley and Finnley was deeply gratifying for Dr. Lauring and her team.

“Ashley had gone from this place of not knowing what was going to happen to trusting us so completely and having such a good outcome,” says Dr. Lauring. “She was always so appreciative of the care we provided and thanked every part of our team. We really bonded over the course of her pregnancy.”

Ashley and Mark are now settled into a new home near her family. When Finnley had his first birthday, they were able have their long-awaited celebration with friends and family. The theme was the Olympics. Ashley had matching t-shirts made, with Finnley’s name and the Olympic wreath, for all the guests to wear. She hung balloons and a banner with monthly photos of Finnley since he was a newborn. “Today is in honor of what Finn’s short, little life has been like,” Ashley said in a speech. “He conquers all challenges, defies all odds and is so worth celebrating.”